Tuesday, April 18, 2017

Thursday, April 13, 2017

Standard Chinese

Standard Chinese

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

For other uses, see Standard Chinese (disambiguation).

"Huayu" redirects here. For other uses, see Huayu (disambiguation).

| Standard Chinese | |

|---|---|

| Modern Standard Mandarin | |

| 普通話 / 普通话 Pǔtōnghuà 國語 / 国语 Guóyǔ 華語 / 华语 Huáyǔ |

|

| Native to | China, Taiwan, Singapore |

|

Native speakers

|

(has begun acquiring native speakers cited 1988, 2014)[1][2] L2 speakers: 7% of China (2014)[3][4] |

|

Sino-Tibetan

|

|

|

Early form

|

|

| Traditional Chinese Simplified Chinese Mainland Chinese Braille Taiwanese Braille Two-Cell Chinese Braille |

|

| Wenfa Shouyu[5] | |

| Official status | |

|

Official language in

|

Shanghai Cooperation Organisation |

| Regulated by | National Language Regulating Committee (China)[6] National Languages Committee (Taiwan) Promote Mandarin Council (Singapore) Chinese Language Standardisation Council (Malaysia) |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

| ISO 639-6 | goyu (Guoyu) |

| Glottolog | None |

| This article contains IPA phonetic symbols. Without proper rendering support, you may see question marks, boxes, or other symbols instead of Unicode characters. | |

| Common name in China | |||

| Traditional Chinese | 普通話 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Simplified Chinese | 普通话 | ||

| Literal meaning | Common speech | ||

|

|||

| Common name in Taiwan | |||

| Traditional Chinese | 國語 | ||

| Simplified Chinese | 国语 | ||

| Literal meaning | National language | ||

|

|||

| Common name in Singapore and Southeast Asia | |||

| Traditional Chinese | 華語 | ||

| Simplified Chinese | 华语 | ||

| Literal meaning | Chinese language | ||

|

|||

Like other varieties of Chinese, Standard Chinese is a tonal language with topic-prominent organization and subject–verb–object word order. It has more initial consonants but fewer vowels, final consonants and tones than southern varieties. Standard Chinese is an analytic language, though with many compound words.

There exist two standardised forms of the language, namely Putonghua in Mainland China and Guoyu in Taiwan. Aside from a number of differences in pronunciation and vocabulary, Putonghua is written using simplified Chinese characters (plus Hanyu Pinyin romanization for teaching), while Guoyu is written using traditional Chinese characters (plus Bopomofo for teaching). There are many characters that are identical between the two systems.

Contents

Names

In Chinese, the standard variety is known as:- Pǔtōnghuà (普通话; 普通話; "common speech") in the People's Republic of China, as well as Hong Kong and Macau;

- Guóyǔ (國語; "national language") in Taiwan;

- Huáyǔ (华语; 華語; "Chinese language") in Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia, the Philippines and the rest of Southeast Asia;[7] and

- Hànyǔ (汉语; 漢語; "language of the Han tribe") in the United States and elsewhere in the Chinese diaspora.

Putonghua and Guoyu

In English, the governments of China and Hong Kong use Putonghua,[8][9] Putonghua Chinese,[10] Mandarin Chinese, and Mandarin,[11][12][13] while those of Taiwan,[14][15] Singapore,[16][17] and Malaysia,[18] use Mandarin.The term Guoyu had previously been used by non-Han rulers of China to refer to their languages, but in 1909 the Qing education ministry officially applied it to Mandarin, a lingua franca based on northern Chinese varieties, proclaiming it as the new "national language".[19]

The name Putonghua also has a long, albeit unofficial, history. It was used as early as 1906 in writings by Zhu Wenxiong to differentiate a modern, standard Chinese from classical Chinese and other varieties of Chinese.

For some linguists of the early 20th century, the Putonghua, or "common tongue/speech", was conceptually different from the Guoyu, or "national language". The former was a national prestige variety, while the latter was the legal standard.[clarification needed]

Based on common understandings of the time, the two were, in fact, different. Guoyu was understood as formal vernacular Chinese, which is close to classical Chinese. By contrast, Putonghua was called "the common speech of the modern man", which is the spoken language adopted as a national lingua franca by conventional usage.

The use of the term Putonghua by left-leaning intellectuals such as Qu Qiubai and Lu Xun influenced the People's Republic of China government to adopt that term to describe Mandarin in 1956. Prior to this, the government used both terms interchangeably.[20]

In Taiwan, Guoyu (national language) continues to be the official term for Standard Chinese. The term Guoyu however, is less used in the PRC, because declaring a Beijing dialect-based standard to be the national language would be deemed unfair to speakers of other varieties and to the ethnic minorities.[citation needed] The term Putonghua (common speech), on the contrary, implies nothing more than the notion of a lingua franca.[citation needed]

During the government of a pro-Taiwan independence coalition (2000–2008), Taiwan officials promoted a different reading of Guoyu as all of the "national languages", meaning Hokkien, Hakka and Formosan as well as Standard Chinese.[21]

Huayu

Huayu, or "language of the Chinese nation", originally simply meant "Chinese language", and was used in overseas communities to contrast Chinese with foreign languages. Over time, the desire to standardise the variety of Chinese spoken in these communities led to the adoption of the name "Huayu" to refer to Mandarin.This name also avoids choosing a side between the alternative names of Putonghua and Guoyu, which came to have political significance after their usages diverged along political lines between the PRC and the ROC. It also incorporates the notion that Mandarin is usually not the national or common language of the areas in which overseas Chinese live.

Mandarin

The term "Mandarin" is a translation of Guānhuà (官话/官話, literally "official's speech"), which referred to the lingua franca of the late Chinese empire. The Chinese term is obsolete as a name for the standard language, but is used by linguists to refer to the major group of Mandarin dialects spoken natively across most of northern and southwestern China.[22]In English, "Mandarin" may refer to the standard language, the dialect group as a whole, or to historic forms such as the late Imperial lingua franca.[22] The name "Modern Standard Mandarin" is sometimes used by linguists who wish to distinguish the current state of the shared language from other northern and historic dialects.[23]

History

Main article: History of Mandarin

Chinese has long had considerable dialectal variation, hence prestige dialects have always existed, and linguae francae have always been needed. Confucius, for example, used yǎyán (雅言; "elegant speech") rather than colloquial regional dialects; text during the Han Dynasty also referred to tōngyǔ (通语; "common language"). Rime books, which were written since the Northern and Southern dynasties, may also have reflected one or more systems of standard pronunciation during those times. However, all of these standard dialects were probably unknown outside the educated elite; even among the elite, pronunciations may have been very different, as the unifying factor of all Chinese dialects, Classical Chinese, was a written standard, not a spoken one.The Chinese have different languages in different provinces, to such an extent that they cannot understand each other.... [They] also have another language which is like a universal and common language; this is the official language of the mandarins and of the court; it is among them like Latin among ourselves.... Two of our fathers [Michele Ruggieri and Matteo Ricci] have been learning this mandarin language... — Alessandro Valignano, Historia del Principio y Progresso de la Compañia de Jesus en las Indias Orientales (1542–1564)[24]

Late empire

Main article: Mandarin (late imperial lingua franca)

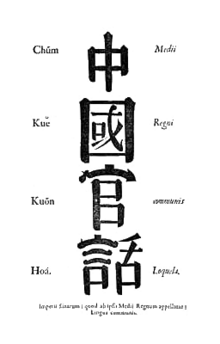

Zhongguo Guanhua (中国官话/中國官話), or Medii Regni Communis Loquela ("Middle Kingdom's Common Speech"), used on the frontispiece of an early Chinese grammar published by Étienne Fourmont (with Arcadio Huang) in 1742[25]

In the 17th century, the Empire had set up Orthoepy Academies (正音书院/正音書院 Zhèngyīn Shūyuàn) in an attempt to make pronunciation conform to the standard. But these attempts had little success, since as late as the 19th century the emperor had difficulty understanding some of his own ministers in court, who did not always try to follow any standard pronunciation.

Before the 19th century, the standard was based on the Nanjing dialect, but later the Beijing dialect became increasingly influential, despite the mix of officials and commoners speaking various dialects in the capital, Beijing.[26] By some accounts, as late as the early 20th century, the position of Nanjing Mandarin was considered to be higher than that of Beijing by some and the postal romanization standards set in 1906 included spellings with elements of Nanjing pronunciation.[27] Nevertheless, by 1909, the dying Qing dynasty had established the Beijing dialect as guóyǔ (国语/國語), or the "national language".

As the island of Taiwan had fallen under Japanese rule per the 1895 Treaty of Shimonoseki, the term kokugo (Japanese: 國語?, "national language") referred to the Japanese language until the handover to the ROC in 1945.

Modern China

After the Republic of China was established in 1912, there was more success in promoting a common national language. A Commission on the Unification of Pronunciation was convened with delegates from the entire country.[28] A Dictionary of National Pronunciation (国音字典/國音字典) was published in 1919, defining a hybrid pronunciation that did not match any existing speech.[29][30] Meanwhile, despite the lack of a workable standardized pronunciation, colloquial literature in written vernacular Chinese continued to develop apace.[31]Gradually, the members of the National Language Commission came to settle upon the Beijing dialect, which became the major source of standard national pronunciation due to its prestigious status. In 1932, the commission published the Vocabulary of National Pronunciation for Everyday Use (国音常用字汇/國音常用字彙), with little fanfare or official announcement. This dictionary was similar to the previous published one except that it normalized the pronunciations for all characters into the pronunciation of the Beijing dialect. Elements from other dialects continue to exist in the standard language, but as exceptions rather than the rule.[32]

After the Chinese Civil War, the People's Republic of China continued the effort, and in 1955, officially renamed guóyǔ as pǔtōnghuà (普通话/普通話), or "common speech". By contrast, the name guóyǔ continued to be used by the Republic of China which, after its 1949 loss in the Chinese Civil War, was left with a territory consisting only of Taiwan and some smaller islands. Since then, the standards used in the PRC and Taiwan have diverged somewhat, especially in newer vocabulary terms, and a little in pronunciation.[33]

In 1956, the standard language of the People's Republic of China was officially defined as: "Pǔtōnghuà is the standard form of Modern Chinese with the Beijing phonological system as its norm of pronunciation, and Northern dialects as its base dialect, and looking to exemplary modern works in báihuà 'vernacular literary language' for its grammatical norms."[34][35] By the official definition, Standard Chinese uses:

- The phonology or sound system of Beijing. A distinction should be made between the sound system of a variety and the actual pronunciation of words in it. The pronunciations of words chosen for the standardized language do not necessarily reproduce all of those of the Beijing dialect. The pronunciation of words is a standardization choice and occasional standardization differences (not accents) do exist, between Putonghua and Guoyu, for example.

- The vocabulary of Mandarin dialects in general. This means that all slang and other elements deemed "regionalisms" are excluded. On the one hand, the vocabulary of all Chinese varieties, especially in more technical fields like science, law, and government, are very similar. (This is similar to the profusion of Latin and Greek words in European languages.) This means that much of the vocabulary of Standard Chinese is shared with all varieties of Chinese. On the other hand, much of the colloquial vocabulary of the Beijing dialect is not included in Standard Chinese, and may not be understood by people outside Beijing.[36]

- The grammar and idiom of exemplary modern Chinese literature, such as the work of Lu Xun, collectively known as "vernacular" (baihua). Modern written vernacular Chinese is in turn based loosely upon a mixture of northern (predominant), southern, and classical grammar and usage. This gives formal Standard Chinese structure a slightly different feel from that of street Beijing dialect.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)